This stereotype is holding back the environmental movement

Minority groups are expected to make up a majority of young Americans in just two years, and become the nation's new majority by 2045. That's good news for the environmental movement – because these groups actually care more about clean air and water than your average middle-class white American does. So do low-income groups.

Surprised? So were we when we recently compiled results for a just-published study on the topic. It showed that all of us – including low-income Americans or people of color – have long stereotyped "environmentalists" as white people with a college education while overlooking the attitudes of groups that ultimately suffer the most from pollution.

Within days of a critical midterm election, this paradox suggests that more people than we thought may bring climate change and other environmental concerns to the ballot box. Importantly, our study points to a huge and untapped opportunity to reach and engage people in the fight for strong clean air and water policies – assuming we do it right.

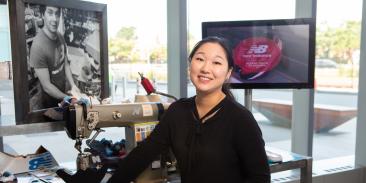

This is what an environmentalist looks like

More than half of Latinos – 54 percent – indicated in our survey that they were "very" or "extremely' concerned about the environment, while 39 percent of African-Americans did. The same level of concern among Whites was just 32 percent. Asians, at 37 percent, also scored higher than Whites.

Not only that: Americans earning less than $15,000 a year are more concerned than Americans with incomes above $150,000.

And still, all surveyed groups seemed to agree that people of color and poor Americans are actually less focused on the environment than their White middle-class counterparts. This belief paradox reflects deep-seated and inaccurate stereotypes that explain, at least in part, why environmental advocacy outreach to minority and low-income groups has historically fallen short.

Lack of diversity perpetuates problem

As many businesses understood a long time ago, to reach an increasingly diverse market you must employ people of different backgrounds. Advocacy groups and government agencies in the environmental space have not yet cracked that nut; to this day, people of color make up just 12 percent of their staff. Similar disparities exist within the environmental sciences.

Meanwhile, local groups that serve communities of color do great work to protect their natural spaces are often not seen as representative of environmentalism.

The lack of visible diversity in the mainstream movement helped shape and perpetuate the image of the typical American environmentalist as a white, well-educated, middle-class person – because it reflected the people inside these organizations.

We need to adjust our message

To raise public engagement and bring millions of new people into the environmental movement, we must – as we continue to diversify our ranks – break down that stereotype and adjust our message for the people we're trying to reach.

Opinion polls and studies, including ours, have shown that rather than trying to increase awareness about environmental threats, of which these groups are already well aware, we need to start from a different vantage point.

It goes like this: We know they know, and we know there are environmental inequalities – a situation we're working to address. We get that climate change and extreme weather affect low-income people more than the rich, as has been the case with Hurricane Harvey and Florence. And that African-Americans are exposed to more pollution than White Americans, regardless of wealth. It's an American problem we can solve together.

Communities of color must share spotlight

All people, including minority groups, need to voice our beliefs and invite conversation that normalizes environmental interests and action. A wide range of research in social, behavioral and health sciences shows us that humans act in accordance with the behaviors and beliefs seen as valued by their communities.

We think it's time to talk more openly about our concerns and take a rightful place in an environmental movement that has room for people from different racial, ethnic and economic backgrounds. Likewise, it's important for those who have been fighting for environmental change to know they may have more support than they think.

It's time for Americans to fight together for a cleaner and more just environment for all. We all stand to win.